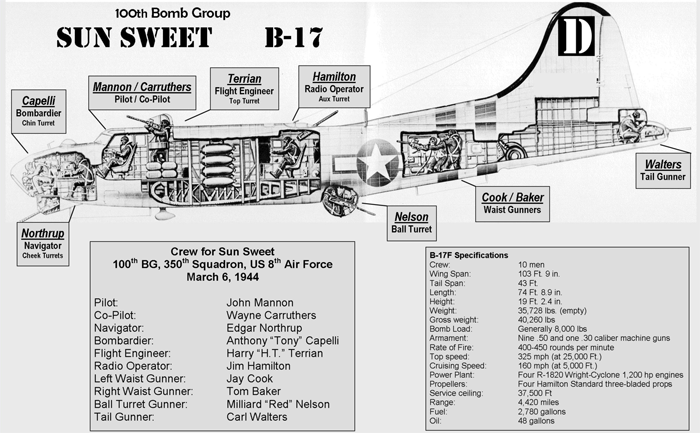

Senator John Mannon's dream, the fierce, recurring nightmare that always involved the harrowing March 1944 crash of his B-17, Sun Sweet, was never less than vivid and wrenching. It was tangible. He could feel the tension, the tremors.

In this dark place, time crawled on bloodied knees, recoiling from the crushing explosions, listening to the howling wind, to the wounded and dying men, all while staring forward or staggering through tunneled, fuselage-green shadows. Somehow, Mannon always managed to fly the bomber, to keep it aloft, but he couldn't keep them together. They needed to jump from him, to fly away.

The realism of the dream and the truth of what really happened that March day was never heroic and certainly not close to the glorified version the media created when bright-eyed journalists produced gushing profiles on the Senator from the great state of Oregon. No, in the darkness of the early morning and in the grayness of real life, the sequence had been gruesome, disjointed. It always took place in slow motion.

For the past 20 years, Mannon's dream even incorporated Red Nelson's saga and the little man getting out of the ball turret, a story retold so often at 100th Bomb Group reunions that Mannon subliminally took on the God-like ability to see from another man's perspective.

That Mannon could see Red, first down in the ball and then later bailing out never made sense, since, after all, it was Mannon's dream and, as the pilot, Mannon had never once gotten into a ball turret. He'd only looked in through the Plexiglas while they were waiting at Thorpe Abbotts for a mission to stage.

The Senator often wondered if it was unusual to conjure up images from two people's point of view. Regardless, most nights, the dream started with Mannon looking down at his watch.

It was 1334 on the 6th and Mannon was squinting through the slanted windscreen waiting for the approaching German fighters to launch their attack. Immediately, he could see the vectoring FW 190, the leader, spitting out rounds from its snarling snout and moments later Sun Sweet's nose bubble exploded just below the cockpit.

The seismic crack was immediate as the German 20mm shells smashed through the Plexiglas cone of Mannon's B-17, unexpectedly blasting Sun Sweet's bombardier out into space. In the moment that followed, a demonic tube-shaped shaft of air ripped through the opened nose, threatening next to push the B-17's navigator out the plane's jammed-open bomb bay doors.

"Someone's just gone out up front." It was Nelson reporting from the Fort's flak-shredded belly gun. "Looks like Capelli. No chute."

Mannon tried not to picture the grisly image but visualized his young bombardier, ripped off the B-17's nose gun, now enduring five miles of twisting, bloody freefall. Their long-prophesied fatal hit, the moment they all dreaded, had arrived. At least they'd toggled their entire bomb load.

"Okay, Har ... Jim ..." Mannon's voice crackled and broke up over the tinny intercom. "Dam - ge - port?"

Despite the violent explosions ringing in his ears, Mannon steadied the shaking, shuddering bomber. He could tell strips of Sun Sweet's dark green sheet metal were ripping off, shooting backwards into the on-coming whirling props of the 351st Squadron.

In that instant, he knew if he couldn't keep up with the 100th's shredded formation, flight leader Bucky Elton would have to leave Sun Sweet behind. They were on their own ... meat on the table for the Luftwaffe.

Mannon's copilot, Wayne Carruthers, watched as a wave of German fighters skidded past them into the onslaught of the 100th's protective aerial box. On Mannon's left, green and gray B-17s blossomed in a bright mosaic of orange and burgundy flames, exploding, still spitting out arcing tracers of dark lead.

Standing above the cockpit, flight engineer Harry Terrian rotated his twin .50 cal machine guns to his left, cataloging what was left of their bomber formation from the top turret. Up ahead were Shoens in Our Gal Sal and near him Lauro and Swartout in Nelson King. But there wasn't much else. It was incredible. They'd been under attack for 25 minutes and the German massacre of the 100th had been nothing short of brutal. At least nine bombers had vanished.

"Heavy nose damage, Cap'n. Jim will have to check the extent of it. Number Two is windmilling. Port side trailing edge is shredded. You can see Number Three's already black." Terrian's scratchy voice betrayed no emotion despite his knowledge their B-17 was doomed. "Four is showing smoke."

Radio operator Jim Hamilton would report in next and Mannon knew the undersized Hamilton was already working his way forward along the narrow catwalk, staggering along the sagging guide rope in the jolting, howling, hissing fuselage. If Northrup was still there, Hamilton would find the navigator sprawled on the other side of the bomb bay sprawled against the nose bulkhead. The gusting wind entering the fuselage from the gashed front would exceed -60°F.

"Electronics out up front ... nose is blown. It's gone. Northy's here ... hit bad ... Tony's gone ... bomb bay doors still open ... oxygen lines ruptured ... crew should grab oxy bott- ..."

"Bandits ... moving into three o'clock high." It was Tom Baker, the port side waist gunner, cutting in with critical information.

Mannon had seen at least three 190s streak past. They'd have snapped off a tight roll and slanted back out of the starboard cloud bank.

"Tail," called Mannon, "How long till contact?"

There was no response.

"How many, Bake?"

"Four, Captain. Here they come."

In the following silence, Mannon pictured each gunner waiting, gauging trajectories. They wouldn't wonder whether Mannon would bail them out. Mannon's mantra for 22 missions had been "aviate, navigate, communicate and then escape." Until he gave the word, they stayed at their guns.

They also knew their physics. Mannon had made sure of that, repeatedly explaining why a B-17 with both wings shouldn't roll over. It was designed to remain "neutral stable" in a dive or simulated dive. And that was his next move ... to push them out of it, bomb bay doors be damned.

****

In the ball turret, Red Nelson knew that unless his Plexiglas bubble cracked open and spit him out, he'd have to crawl up into the bomber's midsection at some point, clip on a chute, and scramble over the spent cartridge shells if he was going to reach the rear waist door.

"For the love of God, Cookie, whaddya see?" Red called out. "I got nothing yet."

"Get ready, boy," radioed Jay Cook, the starboard waist gunner. "They're coming."

Immediately, another shockwave rippled through the bomber.

"They're on us, Cap'n." It was Baker. "Four now at five o'cl- ..."

Baker's scream carried over the intercom and joined with the howling slipstream whipping under the bomber's ball. Sun Sweet rocked repeatedly as the fighters zeroed in on the slowing Fort with the Square D tail marking.

Red was already firing at the fighters as they ran under the plane but he knew there wasn't much time left. Seconds meant everything now.

****

Hunched over the cockpit's steering yoke, Mannon grunted through clenched teeth. If his bomb bay doors were jammed open, he couldn't blow out oil-fed flames with a dive. But he'd have to flash out of formation and fool the Germans into believing Sun Sweet was finished.

He jammed the pilot's control column forward and moments later, as he'd hoped, the four FWs fell away to his starboard and knifed into Brannan's Lucky Lee. The concussive explosions that followed, above Mannon's right wing, were immense.

"Waist, tail, report," Mannon called out as chunks of Brannan's exploding bomber streaked past like Oklahoma straw in a tornado. "Whadda we got?"

"Lucky Lee is in trouble, spinning," he heard Nelson say in the middle of a jarring concussion wave that shook the bomber violently. "Oh, God ... looks like ... she's just lost a wing ... she's going down."

Then Mannon's tinny voice. "Chutes?" he asked despite the clanking from Sun Sweet's return fire.

"Not yet."

"They're done, sir. No chutes." It was Cook. "Bake is hit bad."

Mannon stayed on his checklist despite the immense strain of the diving Fort and his knowledge men were likely dead.

"Top?"

"Clear here."

"Jim?"

"Clear," said Hamilton, now headed aft to check on Baker. He sounded calm.

"Tail?

There was no response.

"Ball?"

"Clear here. But sir, if there's trouble coming, permission to exit ball and man Baker's gun?"

"Granted. Work with Jim to check on Baker and Walters."

****

Red wasn't sure his fatigued muscles would cooperate for his urgent climb into the fuselage. No one could move fast after six hours stuffed in a confining little hole. Hurry, boy. She's gonna blow for sure.

Red rotated the ball around to line up the turret's entry position and reached up to slide open the green trapdoor. It was stuck. There was heavy smoke curling down into his perspiring face from above and he pushed harder against the hatchway.

Steady now. Hold it together.

He could hear Cook sliding over the spent gun shells on the tilted floor above him. Red pressed his throat mic to his neck, "Ball is jammed. Gonna need some help from above."

He said it evenly in his Maine "Down East" drawl, listening for Cook as the waist gunner locked in the manual crank, frantically rotating the emergency release handle.

A muffled voice was shouting, "Get ready, Red!"

When the valve finally curled open, Red, his face crimson from the heat and tension, surged up out of the ball into heaving confusion. There were countless bullet holes and slender flames licking at the plane's innards. Baker was piled against a bulkhead strut as Sun Sweet continued drilling toward the ground with terrible certainty.

****

In the cockpit, Carruthers shouted out gauge readings while Mannon calculated airspeed, engine torque and wing stress.

"You're through fourteen Thou ... 13-5 ... Number Four is maxing ... 13."

"Okay ... yup."

"12-5 ... 12 ... 11-5 ... Oh, my God."

"Stay with me, Wayne."

Mannon yanked back on the stick. If the two remaining engines didn't give out, he might make it. The ground was racing to meet them. If he failed, a nebula of flames would cremate them all.

"11 ... 10.5 ... Ahh, ahhh ...9.5 ... 9."

"Easy, now. c'mon baby ..."

They were slowing.

The building gas in Mannon's stomach exploded up through his throat. Sucking at the stale oxygen from the thin rubber tube that ran along his neck, he turned off his throat microphone. The plane was leveling slightly. There was no time for celebration.

"Wayne, we're down two engines and probably gonna lose Number Four any minute. She's still going down and I can't risk a crash landing on one engine."

"Roger that."

Mannon scanned the land in front of them. For miles, the gray, snow-patched fields of the South Baltic coast were covered with broken-fence fields. Warnemunde, on Mecklenburg Bay, lay to the northwest.

"I can hold her another two minutes, three max. Enough for chutes, but not much more."

"The nose area is gonna be greasy."

"I know. If Northrup's conscious, if he's still underneath us, get a chute on him and push him out. If not, you jump. No heroics. I'll get her level for you and the crew."

They made eye contact as Carruthers stood and unplugged his electrically warmed suit. Both men saw Terrian the grizzled flight engineer coming down from the top turret headed toward the open bomb bay doors. The nose of the plane was underneath and forward of the pilot's compartment and as Carruthers followed Terrian, Mannon guessed the copilot was conducting a quick check to see how much of the plane's front was blown off. There was an enormous amount of freezing air now stabbing upwards at them but Mannon still heard his final remark.

"See you in London."

Mannon grunted at his copilot's confidence without averting his forward gaze. Then he clicked on the microphone, rang the bailout buzzer and with a steady voice commanded, "Bail out, repeat, bail out!"

****

Moving aft in the waist section, Red heard the alert and found his inner voice was remarkably calm.

Stay focused, boy. Get yer chute on. Grab Baker. Man, look at the blood. Push him up toward the door. Follow Cook. Pull Baker's ripcord and push the sonuvabitch out. Get going yah big crackah. Now, we jump. GO ...

****

Mannon didn't know how many chutes went out but hoped they'd had enough time. They were still above 3,000 feet and 1,000 was supposedly the bare minimum. He released the microphone from around his neck, tossing it on Carruthers's empty seat. Hearing a series of detonations behind him, Mannon flicked at the fuel boost pump switch. His flaps and wheels were up.

His eyes darted along the console housing, moving from the altimeter to his indicator dials. Methodically he checked the turn, flight and banking gauges. The flight indicator gyro heaved rhythmically as his craft pulled to the right. Mannon slapped at the rudder pedals like a drunk at a piano, but knew the bomber's massive tail was shredded. He moved his right boot back until it rested against the elevator-locking lever.

Adjust elevator trim tab. Watch the pitch.

The plane slowed its descent but Mannon's mind continued through the proper sequential movements.

Oil and temperature levels maxed. Shut-off fuel valve. Lock cowl flaps.

For the first time, he heard the roar. The sub-zero wind rushed under him and reached for his thick neck. She was down to 2,100 feet and the two remaining engines howled like gutted, wounded beasts.

Not much left in them now.

Mannon conjured up images of 100th pilots Flesh and Gossage who, fearing an in-flight explosion, bailed their entire crew out over enemy territory before combining to fly their bomber back to England. It never blew. At the base, the two pilots' aerial performance in the shot-up B-17 was labeled heroic but Flesh knew he'd put eight men down behind enemy lines and hadn't known which ones made it.

Gotta get Northrup's dog tags ... if he's still there.

At 300 feet, Mannon shoved both rudder pedals to the floor and pulled himself up on the wheel. The half-standing position gave him one last glimpse and revealed uneven ground along a flat, open plain. He didn't think the plane would slide far enough to reach a distant tree line.

He was soon under 150 feet and from the side window he saw patches of grayish snow. He eased back on the throttle, closed off the fuel lines and, protecting his ribs with his elbows, brought Sun Sweet down.

The first touch snapped the plane back off the ground. Seconds later, the midsection of the bomber collided with the rock-hard field, gouging a lengthy furrow through ice and frozen mud. Mannon saw one propeller tip rip off as the crumpled nose bounced violently upward. He knew underneath the plane, the ball had been obliterated.

The veteran pilot turned his head to avoid the flying glass dials from the shattered cockpit panels. As the massive bomber ground to a halt, Mannon hoped his men got out in time. If they had, they'd need a miracle getting home. So would he.

And then, as he always did, Mannon sat bolt upright from his dream. The sheets around him were soaked, his brow and the back of his neck pushing out a swampy tidal surge of sticky sweat.

God, not again.